-

Exhibitions

- Keeping Score | Neerja Kothari

- Neerja Kothari

-

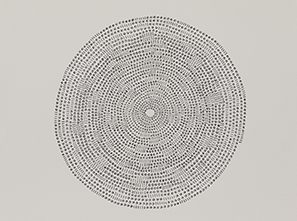

Manuscript for the Book of Time – Subset 1 – 21 days

Manuscript for the Book of Time – Subset 1 – 21 days

-

this mark repeatedly (31500)

this mark repeatedly (31500)

-

this mark repeatedly (45310)

this mark repeatedly (45310)

-

this mark repeatedly (50100)

this mark repeatedly (50100)

-

this mark repeatedly (16312)

this mark repeatedly (16312)

-

gesture, by the last vibration of the singing bowls (6352)

gesture, by the last vibration of the singing bowls (6352)

-

gesture, by the healing vibrations of the singing bowls (15636)

gesture, by the healing vibrations of the singing bowls (15636)

-

to the notes of 10s and 11s (II)

to the notes of 10s and 11s (II)

-

to the notes of 10s and 11s (I)

to the notes of 10s and 11s (I)

-

to the notes of 10s and 11s

to the notes of 10s and 11s

-

to the beats of 10s and 11s

to the beats of 10s and 11s

-

to the score of 10s and 11s

to the score of 10s and 11s

-

one slow moving gesture of 11 minutes

one slow moving gesture of 11 minutes

-

silent gestures, once the music stops

silent gestures, once the music stops

-

this mark repeatedly (68300)

this mark repeatedly (68300)

-

this mark repeatedly (61673)

this mark repeatedly (61673)

-

this mark repeatedly (62700)

this mark repeatedly (62700)

-

this mark repeatedly (46222)

this mark repeatedly (46222)

-

this mark repeatedly (66309)

this mark repeatedly (66309)

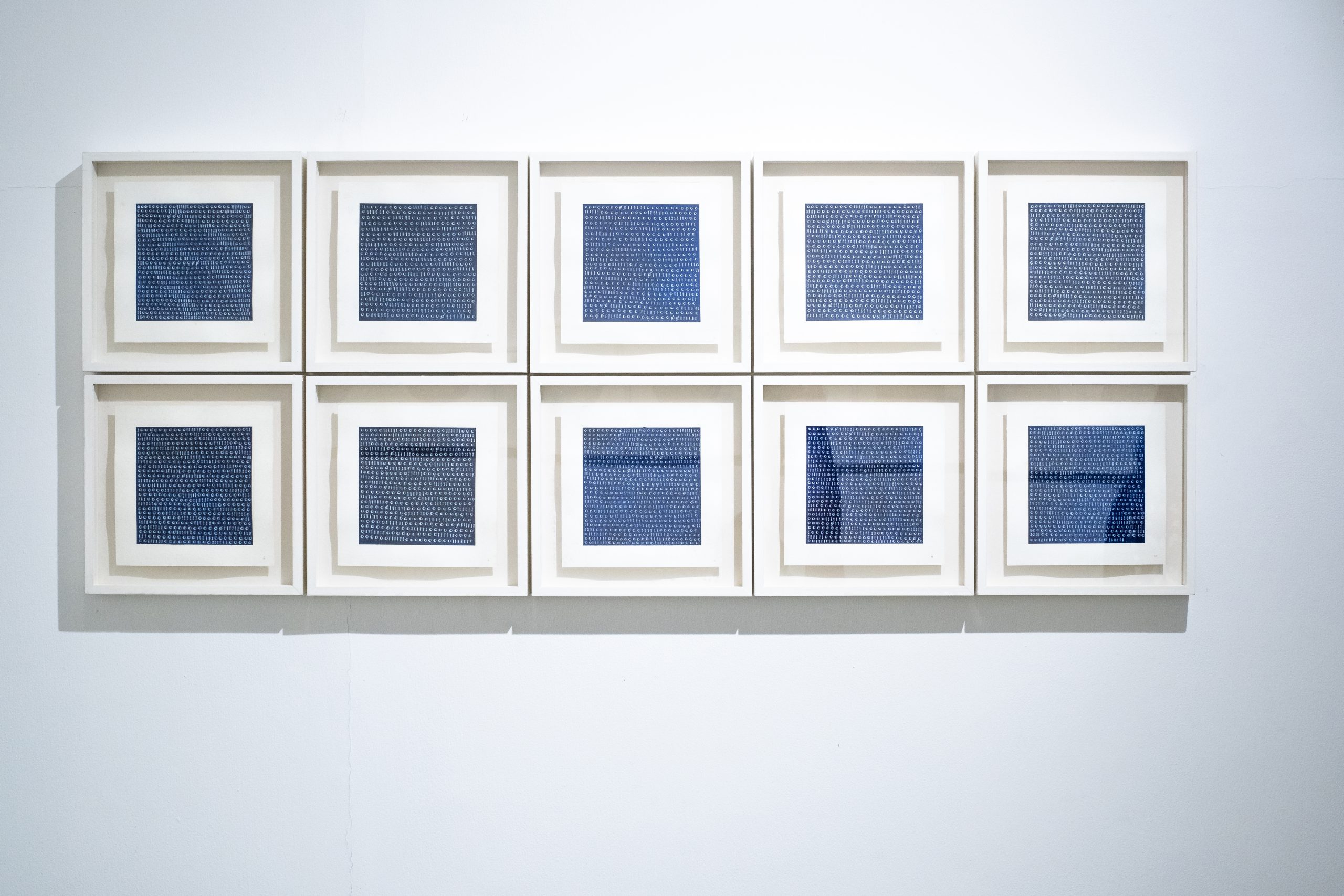

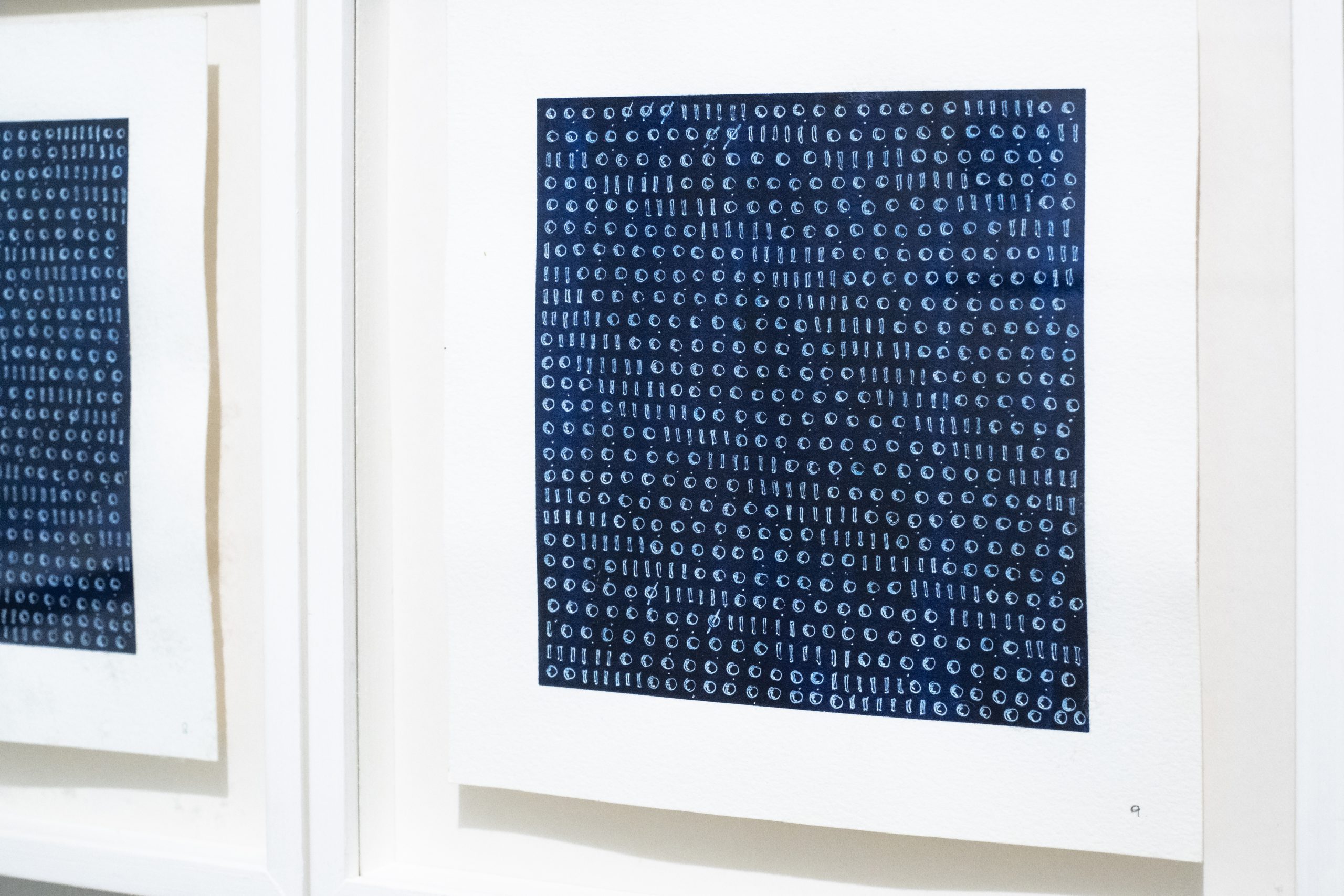

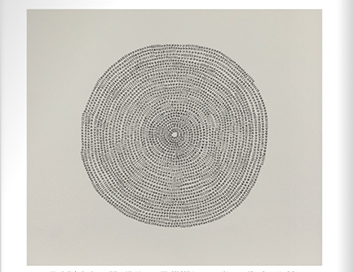

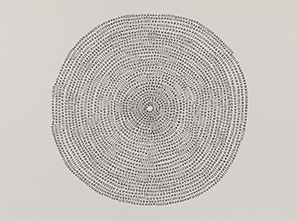

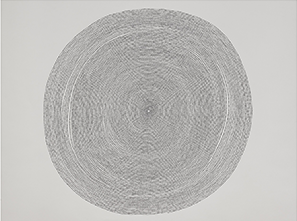

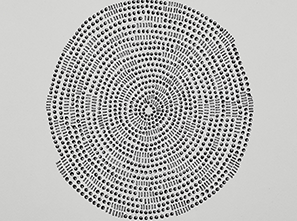

With Keeping Score, Neerja Kothari revisits the fundamental aspects of her artistic practice —

the inadequacy of the empirical or the absurdity of scientific certainty easily countered by

metaphysics the glaring gaps it presents— with new bodies of work. „Score‟ takes on the twin

meaning of a musical score, an homage to the extent to which music has helped her with pain

management, and also the meticulous count that she keeps of every muscle movement during

laborious physiotherapy — at first to salvage the function of her muscles and later, to regain and

maintain it. The irony of relying on empirical logic to relearn whimsical, intuitive movements of

the body that most of us take for granted with relative effectiveness, as experienced by the

artist, forms the crux of her practice. The two bodies of work, To the notes of 10s and 11s and

To the beats of 10s and 11s, capture the title of the exhibition accurately. Shedding abstract

pictorial (numerical) representation of numbers, the artist chalks a circle, or what appears to

resemble a new moon for the ten cycles of an exercise completed, and the staccato of a short

line to render the moment her gluteus maximus — the largest muscle in the human body —

froze, confirming motor sensory neuropathy. She attempted the 11th cycle three times in vain

before giving up. This traumatic memory etched upon her body cathartically plays itself out in a

loop in these drawings, winding around itself like a vinyl record coded with different notes even

as it maintains the optics of consistency. This body of work started with the series of similar

representations marked continuously on 11 pieces of paper, over 11 layers of blue ink.

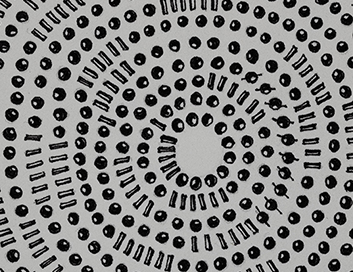

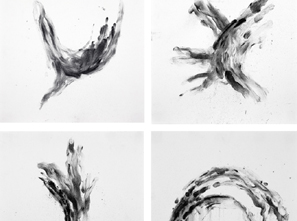

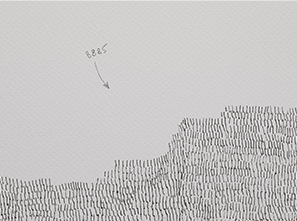

The two bodies of work, a series of „gestures‟, and This mark repeatedly function together as

countering forces that defeat empiricism in one strike. The series of gestures capture in traces

of graphite powder, the artist‟s hands moving to either the John Cage composition, 13

Harmonies listened to until the 11th minute or the complex tonality of a Tibetan singing bowl

which she frequently revisits for relief during attempts to drown the cries of her own body.

Kothari then counts every speck of graphite that is visible to the naked eye on the surface of the

paper, and numbers each and every one of them, resulting in an act that is absurd and

meaningless; she reduces poetic actions to mere numericals to mirror the experience of paring

down every meaningful movement that the body is capable of to repetitive, sparse actions. In

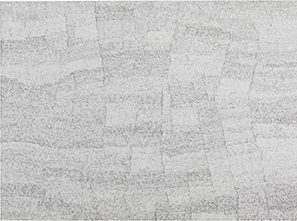

This mark repeatedly, on the other hand, instead of starting with the amorphous, as the title

suggests, the artist methodically makes repeated perpendicular lines that are of the same length

over and over again to result in what almost seems to be a rugged mountainscape, quite by

chance, revealing the nebulous terrain of repeated learning and unlearning, and also the

breakdown of it. Once again she reveals the pretentiousness of any sort of measure or scale

which must either lose sight of the interstitial states of being or is completely oblivious to the

macro-perspective. It is this existential in-between that Kothari treads every day while keeping

movement alive in her body.

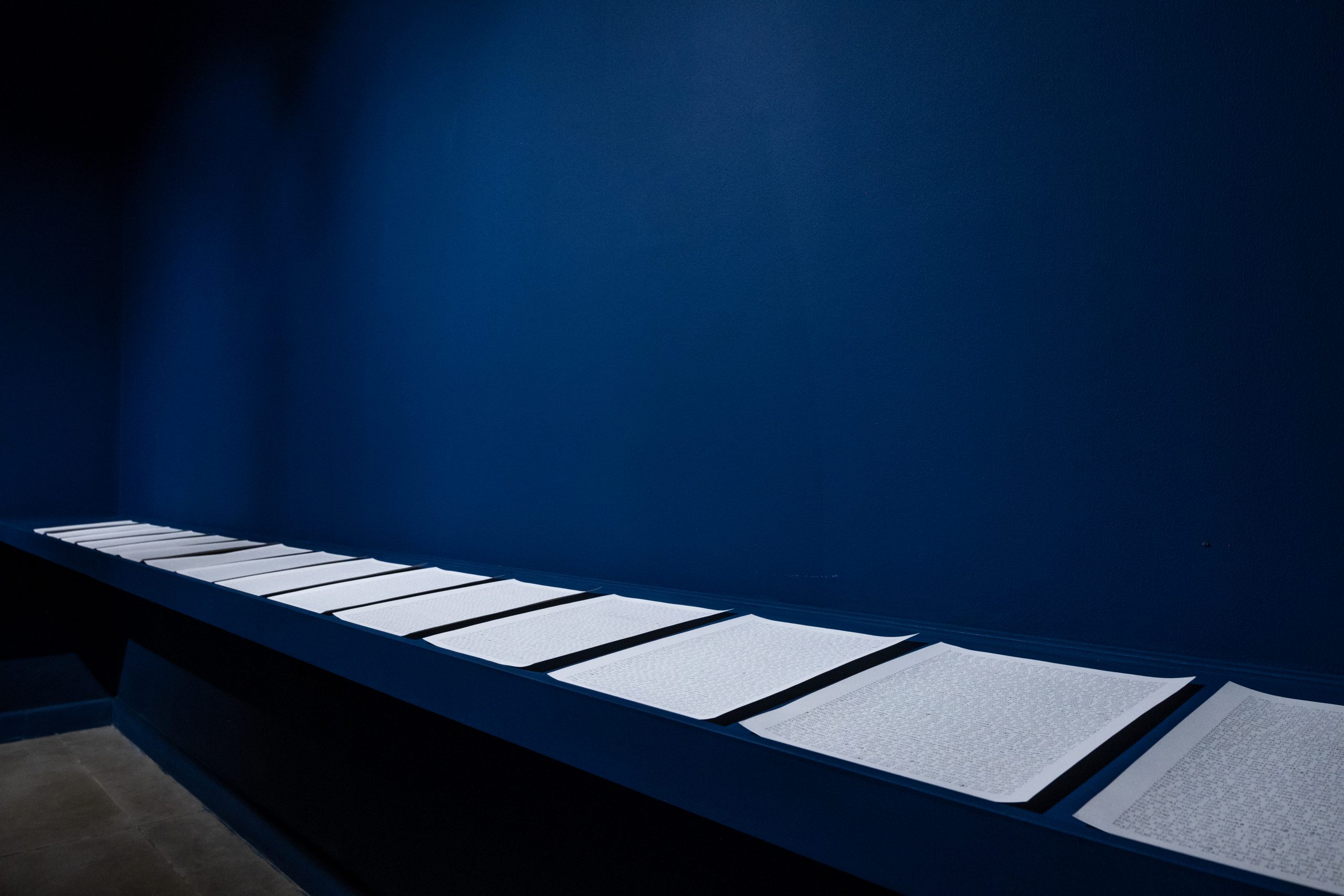

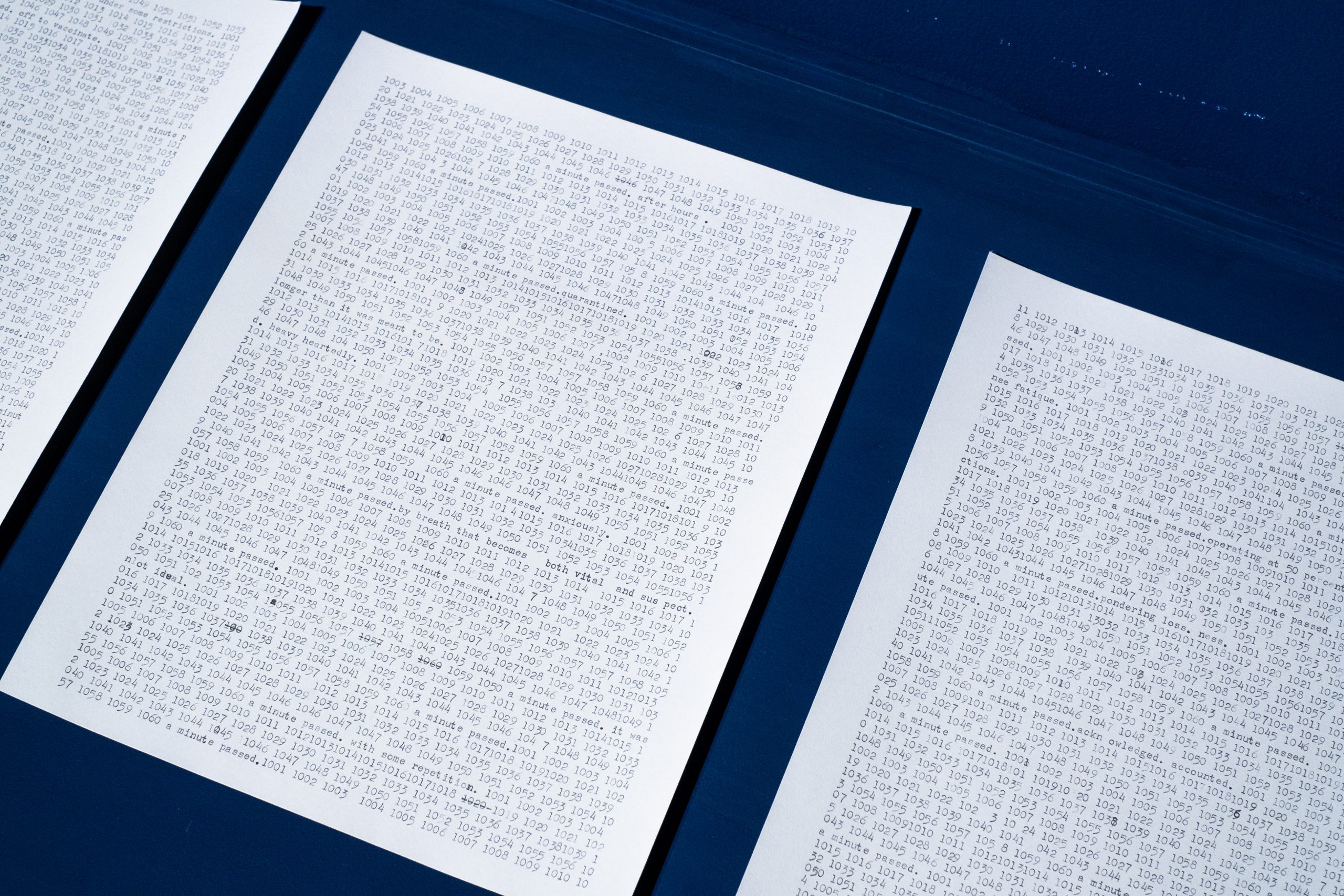

Her most recent work, Manuscript for the book of time: Subset 1 – 21 days inspired by the

tumultuous passing of time during the ongoing global health crisis is a performative manuscript

where the artist has recorded the passing of time from confinement, often while passively

listening to news stories on the television that quantify the pandemic, loss of lives and

livelihoods in numbers, statistics and its economic consequences. In physiotherapy sessions,

she was taught that one second is equivalent to the time it takes to recite the words, “Thousand

and one”, as one method to hold a posture for the desired amount of time. Armed with a ticker

and this bodily metronome, she has set out to measure the time, also recording the minutes of

rest and lapses in this tedious, repetitive process over 21 days.

Albert Camus wrote in the Myth of Sisyphus: “Men [sic.], too, secrete the inhuman. At certain

moments of lucidity, the mechanical aspect of their gestures, their meaningless pantomime

makes silly everything that surrounds them.” To illustrate, he describes the experience of

observing a person on a telephone behind a glass partition, where you are unable to hear them

but are witness to their emphatic gesticulations. By breaking down her visual vocabulary and

artistic process down to their essential formal logic in her works, Kothari places her viewers at a

similar vantage point where the „real‟ that saturates the world around us and civilizational

processes of meaning-making that we take for granted are derealized, and thrown into question.

The inevitability of human error is another subtle cue that has always been consistent in

Kothari‟s practice. The irony of her faux-methodical process is heightened as she leaves the

errors in her calculations in the work, without masking or erasing them. As we view her work at

a time when we are paying dearly for the oversights of scientific development, a cherished linear

trajectory we have fastly held on to and pursued since Enlightment, disfavouring indigenous

wisdom and oral narratives pliable to time and perspective; when right wing religious

organizations tout development and industrialization as trump cards; we wonder, were the

warning signs everywhere? How complicit are we when we neglect delicate ideas of care and

sustainability for the mathematical approximations that feed capital? Space travel was the

battlefield during the Cold War, as an assertion of supremacy. If technological advancement

was/is the logic of war, is there another logic for healing?

— Text by Anushka Rajendran